Janel Jacobson - In Her Own Words

You began as a carver of beautiful, intricate shapes in clay and then transitioned to wood. What was it that called you to move to wood as a medium?

You began as a carver of beautiful, intricate shapes in clay and then transitioned to wood. What was it that called you to move to wood as a medium?

During the five year period in which I explored carving 3 Dimensional small sculptural pieces, netsuke and ojime from porcelain clay, various things became apparent to me that encouraged me to make the change to wood for carving.

Back then, I carved slightly damp porcelain clay, having done so for several years before with shallow relief carving on low, slightly domed surfaces of small, lidded containers. While holding the 3-D small sculptures, the side being held would become slightly altered and would need recarving as the piece was rotated during the carving process. Eventually the damage would cease as the clay dried, which allowed the final details to remain intact. This was a frustration, but surmountable with patience.

To glaze or not to glaze was always the question. Unglazed porcelain could range from white in an electric firing, to a slightly grayed white in gas reduction firings. The unglazed surfaces needed significant sanding to produce a luscious and tactile surface. The pieces that were glazed needed to have a "foot" that was unglazed to prevent the glaze from sticking to the kiln shelf. Such a thing may not compliment the composition and was tricky to work around.

Unglazed pieces allowed the light and shadow to play across the sculptural surfaces. Though they felt nice in the hand, I found that people would not reach to receive a piece nearly as eagerly as one reaches for a piece of carved wood. Glaze hid the sculptural affects of light and shadow, and did not adequately respond to the subtle colorations of glaze as the shallow relief carved lidded dishes, partly because the glaze flows in response to gravity and would pool differently on vertical surfaces.

For me, the results from either finishing method were not satisfactory.

I began to ask questions of woodworking and carving artists about tools and materials. I also attended International Netsuke Society conventions and began to see how varied and warm small sculptural pieces could be that were of wood or ivory. The cool and hard porcelain pieces were not nearly as warmly received as were the pieces carved from the organic materials.

Finally, having returned from a show in late spring of 1995, I began working on a new porcelain sculptural piece that cracked after some hours of work were invested in it. For the first time, I threw the piece into the waste can, and took out a piece of boxwood that a friend had sent to me as an incentive to try carving wood. It worked.

I began carving wood from that moment forward. I made a tool and then bought a small set of miniature carving tools and spent the summer beginning to discover the joys of carving wood.

With pottery I would guess (although I of course could be wildly wrong ;) ) that if you made a mistake you could just add clay to it and try again. With wood it would seem that any tiny mistake is permanent. Is that true and does that shape how you work on a piece?

With pottery I would guess (although I of course could be wildly wrong ;) ) that if you made a mistake you could just add clay to it and try again. With wood it would seem that any tiny mistake is permanent. Is that true and does that shape how you work on a piece?

For quite a while with porcelain I did use a technique where I would carve the surface underneath where legs and antennae would be for katydids and legs of long legged spiders for instance. I would put thickened slurry onto a scored line that would then be carved into the finest raised lines. This was one use for adding back clay. And yes, it also worked to fix a mistake though I tried to not make those.

When I began to consider carving wood, I began to force myself to use only subtractive carving techniques with porcelain. This method was more difficult, but was a very good exercise for future work in wood and other organic materials.

Wood is less forgiving in that way, and on rare occasions a piece may not be completed. With my carving technique, the detail work progresses slowly. There is time for thought and mental preparation when increasingly more care is needed. Knowing when to turn off the audio book or radio is one skill to have to enable clear focus; another is to not approach a tricky part when tired or distracted.

Do you have a mental image first, and then find a piece of wood that suits that image, or do you start with a gorgeous piece of wood, examine it for a while, and see what shapes come to mind?

Yes, both approaches. Decisions are made according to the circumstances: what sort of time is available to complete a piece; perhaps I have no pieces with frogs as a main subject (I like tree frogs and toads); am I ready for a significantly detailed piece or for one that has a simpler composition.

If I have decided on a specific form and composition, I then ‘shop’ for the wood, rummaging through boxes sent by wood working friends (their scrap is my resource as in

one person’s trash is another person’s ‘treasure’), and through the materials that I have purchased. Doing so, I envision other concepts in some pieces and may note the piece for later consideration?

Or I might simply begin ‘shopping’ through the wood and may eventually see a composition in the shape of the wood and the evidence in the grain and coloration of the wood that might add to the composition?

Or determined to use a specific piece of wood, I will contemplate its use while working on other pieces, or I will work on a composition plan until it is ready for carving in the selected wood.

I am about to use this scenario with my next piece. I have: looked at a small piece of Mountain Mahogany for a few months while working on other projects; have gathered photographic samples of the subject (a ocean creature that does not live in the Midwest so no living models possible); have made cursory sketches and have made a modeling clay form to begin to understand the shape to be carved. I have not always used the modeling clay method, but it is helpful to begin seeing something in 3-D before removing wood.

Do you keep a notebook or folder with the various ideas you come across in your life, and use those when you are ready to start a new carving? Or is it always something fresh each time?

Yes, both again. Before parenting commanded a significant portion of my time, I had much more time to draw leaves, branches, flowers, insects and critters. During those recent two decades I did occasionally draw to help me understand the form, shading and detail of things that interested me. With our child away at college, and all of our parents now at rest, I look forward to adding drawing back to my exercises and pleasurable exploration activities.

These earlier drawings have been a great resource for understanding what is ‘characteristic’ about a particular subject and have been used as a guide when carving those subjects. I store the drawings in a file box at the carving bench.

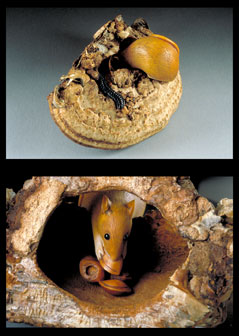

The work "Chestnut and Peeper" is absolutely lovely, you really get a sense of the texture and life of each of the two characters. What research do you put into the items you carve?

In my studio I keep gray tree frogs and spring peepers. In addition, I have had toads, a snake and salamanders. To feed the amphibians I raise crickets, and for a while I bred mice to feed the snake. Every one of those critters became subjects for carvings at some point in time, crickets and mice included.

The tree frogs are marvelous to observe, and even though drawing them can be challenging, I will from time to time try to capture a particular pose on a branch or a leaf. The chestnut was carved using a real chestnut as a model, which is often the sort of research habit I use when leaves, flower buds or branches are available.

When I look at "Butterfly" it is almost as if the wings are transparent. Then you have pieces like "Reflection" where you create the illusion of water. What challenges are there in fooling the eye into seeing different types of surfaces?

When I look at "Butterfly" it is almost as if the wings are transparent. Then you have pieces like "Reflection" where you create the illusion of water. What challenges are there in fooling the eye into seeing different types of surfaces?

I look at the wood and its grain patterns as I consider what to use and for what the subject is that is to be represented by it. Surface treatment can either enhance the chatoyance and grain of various woods, or diminish reflectivity to add contrast to texture and depth to the carving. The secondary color in the particular piece of Ebony for

"Butterfly" appeared when I cut this slab of wood from the block. Immediately I recognized the butterfly that appeared when I separated the wood pieces. I chose to enhance the shape with an inlaid butterfly body from another Ebony source and determined the outline of a sort of butterfly that has a similar coloration and characteristic. Upon smoothing the wood, and adding the finish, the subtle variation in the wood grain appeared. The challenge with the surfaces of the piece "Butterfly", the Ebony is very dense and fine grained. It can take a very high gloss sanding and polish, which means meticulous sanding and polishing using up to 12,000 grit emery cloths to remove the even the finest marks.

"Centipede" is another example of Ebony that shows contrast between high polish and a dulled surface, chosen for greater effect.

"Red Lily" has an amazing interplay of textures and colors. It says that is all from boxwood - are they different pieces that you connected together? I imagine you had to dye or paint the lily part?

"Red Lily" was carved from a single piece of boxwood. The amber eyes are inlaid. Considerable care was taken while carving this piece that includes two frogs with textured skin, an opening lily bud with six petals, four inlaid eyes and about 25 individual toes. The color for this piece was artists’ oil paint.

Traditionally, netsuke were toggles to hold little bags / boxes. So in our modern world these would be similar to, say, zipper pulls. When you look at older cultures, often these little details would be items of beauty - carved buttons, elegant netsuke, and so on. In our modern culture it sometimes seems we don't give them much thought at all. The buttons are mass marketed plastic items. Are we losing a sense of the value of the small things in life?

As a means for attachment, small netsuke are sometimes used in these times to hang a cell phone from one’s belt. Netsuke were truly functional objects. As the ability to hire the carving of netsuke for particular uses and with selected subjects, they became very popular and more ornate. When western dress was adopted in Japan the use of netsuke faded away. At some point, netsuke became a popular item for collectors, the habit extending into today. Because the resources for old netsuke are limited, good yet affordable netsuke have become harder to find, thus the rise of mass production for cheap tourist items. There is a charm to any netsuke, for there are as many kinds of tastes for things as there are people. Living, serious, netsuke carvers strive for excellence in composition, potential function and subjects. These carvers are relatively few in number when counted against the number of other artists in the world. So too are the collectors relatively few in number who help the netsuke carvers to support their way of.

I am not sure if "we" who live in this present age of computerized everything that you can think of, are losing a sense of the value of the small things in life. My own life has run parallel to the greater world, with a desire to be aware of the natural world where I live in rural Minnesota. Perhaps I am not completely able to answer this question. I hope that with my work, as people see it, they will be reminded of an encounter with something from earlier in life, or will regain a sense of a separate, slower and quieter place to retreat to when holding or viewing the small things that I have carved.

Many of our readers are artists who hope to someday sell their works. What advice would you give to someone who has a niche product and is hoping to gain an audience for it?

Many of our readers are artists who hope to someday sell their works. What advice would you give to someone who has a niche product and is hoping to gain an audience for it?

This is not an easy question for me to answer simply. I will offer some ideas (For visual artists):

- Talk with other artists about their approach to presenting their work for sale.

- Decide if you want to: supply galleries with work for consignment or wholesale; or market you work yourself at shows.

- Travel to shows that may attract the sort of audiences who may be attracted to your work.

- Do your research on, and perhaps visit, galleries that may be able to represent your work.

- Create a web presence: a web site with yourname.com; develop social networking visibility using the growing popularity of this new angle to advertising.

There are many ways to sell one’s work: through galleries; local, regional or national outdoor or indoor art or craft shows; the Internet; representation by dealers; owning your own shop; or private presentation to specific clients to name a few possibilities.

My experience over the decades has been with doing shows that promote excellence in American Craft, whose artists have gone beyond the "craft" of art. The shows that I attend now are indoors and are considered the top shows in the national Craft/Art arena. I have had work in galleries, themed gallery exhibitions, group and solo exhibitions in galleries and museums. I attend a biennial gathering of netsuke collectors and carvers, which is one particular niche where some of my work fits in.

What I have seen some artists do is to visit the potential shows that may be appropriate for their work. If you attend a show to learn from it and the artists, please be aware when speaking with the artists that they are there to connect with clients. Be ready to step aside in the midst of a conversation to allow the artist to do their work. It may be fruitful to ask if the artist is willing to communicate after returning home if you need more detailed information. You may also visit galleries that might successfully represent your work. It may be a good idea if you intend to meet the owner or manager to be prepared with information about yourself and your work.

After decades: of doing shows and selling from the studio; a presence on the internet since 1997; email communications; photo representation changing from slide and print to digital; and hosting a web forum; I have awakened to the recommendations that seasoned artists are being strongly urged to learn about and to jump into the social media arena. Other artists are already doing so. I must pursue this advice, but have resisted it until now because the computer already commands a large portion of each day, and the studio work suffers as a consequence. Apart from that, it is noteworthy to be aware of the fact that the way we present and bring attention to our work in the present and near future has been changing and that there are now more and more people who shop on the Internet, art work included. My customers almost always have purchased work after seeing it in real life, so this movement towards Internet selling feels like it might be an irregular fit at first.

Raising awareness of one’s work, with resulting sales is the goal. I don’t know what the best way to do this is, but the urgings from organizations established to counsel artists are now presenting the social media concept to us in group presentations. Posting images, writing about yourself and work, and video content on the Internet are all means for spreading information about what you do. The key is that you present it and others will spread the word, which then directs attention to your web site and other promotional sites that present your work.

In spite of the considerable amount of time required to being at the computer, I still desire to work in the studio. All I wanted to do in the past pre-computer decades was to be in the studio and pursue what I loved doing. The computer age has significantly changed the balance. As a self-employed no other employees business, all aspects of creation, documentation, promotion, selling, bookkeeping and all else, are part of my job description (along with home and family responsibilities). This was not part of my education when initial movement in college was taken towards becoming an artist in the early 1970’s. I hope that there is more training in the pursuit of management, survival and success as artists before young artists step into the world to work on their own.

Finding an audience for a niche product might be simple or complicated, depending on what it is you are creating. If you approach your decision to create something in response to an audience need there may be an audience ready to support your work. If you choose to follow your passion and hope an audience will both love your work and be able to support what you do, you will be a lucky gambler. I feel like the latter describes my creative path with the work I have been doing in the past decades.

How long, on average, does it take you to complete one of your works of art?

One week to eight weeks. I do not manage to carve for a whole day most days; there are other work related tasks involved in the whole picture of what needs doing. Some days I am able to carve fifteen minutes, other days for nine hours. If all goes well a good day is four to seven hours, or as long as my hands can tolerate the work.

You of course don't have to answer this next part, but many of our artists struggle with how to handle pricing issues. I noticed you don't list prices on the website. What is the reason you don't show the prices? Wouldn't listing prices then ensure you only get serious inquiries about your items?

Those are very good questions to ask.

Pricing is an extremely difficult subject for me to find any perfect solution to. I struggle with the need to survive financially and how to put a price on the work I do. There are different approaches and considerations that any artist can take to arrive at a price: what the general market (your peers) are selling their work for; what clients are willing to pay for the work; what you need to not only survive financially as a business owner; allow for growth in your work; to have a personal/family income; and be able to pay back loans or contribute to savings for your older years, and health insurance, to name a few.

For a long time, my approach has been to record the number of hours spent making each piece. Periodically to reassess pricing, I gather information from business and personal expenses for a few years. An estimate is made for how the hours of the years are broken down: days/weeks involved in preparing for and being away from home at shows; desk and computer work for communication, bookkeeping, show applications, digital imagery, the taking and preparation of images for web, print, show applications, etc.; average in weeks for sick time, family needs, holidays, emergencies; and the carving time that might be possible to create the work destined for selling. Then the mathematical relationship between the actual time recorded for completing work is applied to the amount of income required for survival or financial growth, family income and personal expenses for one year. What never seems to be factored in is the time spent working at the desk and photographic documentation, etc., which when applied to the equation (theoretical equation) reduces the dollar per hour factor considerably.

The goal of this work is to arrive at a dollar per hour factor that is applied to each total carving time, which helps with estimating a price for each piece. In theory, this should be the wholesale price. The current work in wood takes a great deal of time to complete, so the prices have grown to be very high figures while remaining the "wholesale" amount. This makes it very difficult for me to consider selling wholesale or consignment through galleries, because I also sell my work myself and incur the travel and show expenses, and the promotional fees attendant to that activity. A keystone or keystone plus price would not seem realistic when looking at the scale of the work I do. (I often wonder if there would even be a question of retail value in relation to scale if as many hours were put into my sculpting a larger piece?)

So roughly, all of the expenses for business and personal needs - divided by - the estimated hours that might be spent creating the works in a year might produce a base line price for the $/hour factor to be applied to the sum of hours spent on each piece. $/hour x number of hours = the price you need to survive if all of the work sells. It looks like a high price per hour, but immediately that high figure is diluted by the number of hours spent with photography and email and web site and forum work and soon to be added social networking for work promotion. At this point, I average up or down to a round number, and I may add a percentage if I know that clients might ask for or expect a discount.

My peers all approach pricing differently. I have never been able to figure out how to use a different sort of formula for arriving at a price for my work. The material cost for the small pieces I carve is negligible. Overhead is substantial, and business and personal income is dependent upon sales. The accrual of 20 to 250 or more hours in a piece is the real drive to determine fair pricing for financial survival.

Pricing. I hate this part of my job. I would rather be carving.

The past two or three years of economic upheaval have been extremely difficult, causing me to question everything about pricing, and also whether or not I should work as I have been with the work in wood. Trying to write about that would be to move on to a different topic, which I will not address at this time.

In answer to your question, I have tried posting prices for my work on my web site and I received no communications of interest from anyone. At least with no pricing on the web site, I receive inquires and have the opportunity to meet potential clients and discuss the work with individuals interested in what they see. It is the same at shows. If I placed prices by each piece, all I would hear all day would be, "Nine Thousand Dollars!!!!! It is only a small piece of wood, how could it be so expensive?" I would much rather experience every person falling in love with each piece and then gently inform them of the prices if they are interested. It seems to be a much more respectful approach. The shows I attend have a higher proportion of collectors in the audience, so there are actually people who are more likely to understand what has gone into the small sculptures and why the large prices exist.

What other words of wisdom would you share with artists who are seeking to become more established?

My favorite quote, since 1975 or before:

What you can do, or dream you can, begin it; Boldness has genius, power and magic in it. ~ Goethe ~

To see all of Janel's gorgeous artwork, visit her website:

Janel Jacobson Website